Is Your Tap Water Safe? Here’s What I Learned After Testing Mine.

We drink it, cook with it, and bathe in it—but do we really know what’s in our tap water? I tested mine in LA and NYC, and the results were…eye-opening.

The Growing Concern Over Microplastics

Remember when the headline about microplastics in bottled water ripped across our feeds and media outlets? I do, because I helped to cover that story when I was the Chief Medical Correspondent for ABC News.

Did you know you consume (on average) a credit card’s worth of plastic every week? This problem has become so pervasive that microplastics have been found in Antarctic snow and newborn babies.

As a doctor and medical journalist, my first thought was, “Finding microplastics in our water doesn’t sound great, but how much of an actual problem or risk is this, really?” As a water consumer, my initial reaction was, “Ugh, I don’t drink enough water as it is—NOW what do I do?”

Why Testing Your Water Matters

Well, as a person of science, my response was to launch into experiment/testing mode. My first step was to get my tap water analyzed; because I am bicoastal, I decided to do this in both New York City and Los Angeles. After all, our adult bodies consist of around 60% water, and our brains are 80-85%. A newborn’s body is fully 90% water. You can go a long time without food, but you cannot survive more than 3 days without water.

Did you know the CDC recommends that people with well water periodically get their home tap water tested? I was not aware of this until I did it, though I don’t have well water. According to CDC guidelines, it’s recommended that you test your well water at LEAST once a year to check for total coliform bacteria, nitrates, total dissolved solids, and pH level.

Where you live is important, so check with your local health department to find out if there are other chemicals or organisms that should be included in a test. If you use a non-commercial company to process the specimen, make sure you use a state-certified lab to test your water.

Your health department should be able to help you interpret your testing results and answer any further questions you may have on your report.

How Water Quality is Regulated

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulates public drinking water (tap water), while the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates bottled drinking water.

In the U.S., the Clean Water Act (1972) and the Safe Drinking Water Act (1974) are the main governing laws. In 1976 and 1986, the EPA published the Quality Criteria for Water—known as the “Red Book” and the “Gold Book,” respectively. The criteria in these documents are still current. There have been some recent recommendations, but absolutely no new laws. Click here for more details.

The Pros and Cons of Testing Your Tap Water

Testing your tap water has its pros and cons. Potential benefits include:

- Identifying harmful contaminants like lead, bacteria, pesticides, or heavy metals that may be associated with health risks.

- Ensuring your water meets basic safety standards and provides information that might make you more confident about the quality of the water you and your family consume.

- If you notice an unusual smell, taste, or color in your water, testing can help identify the problem. Periodic testing of older plumbing systems or private wells can also uncover contamination issues early and help you avoid more extensive repairs and health problems later.

And the cons? The cost, for one. Here are estimated price ranges (though depending on where you live, they may be higher):

- $100 – $500 average well water testing cost

- $250 – $550 average well inspection cost

- $400 – $650 average well & septic inspection cost

Cost may be an issue, yes, but the environmental health of your home should be a financial priority. In my opinion, it’s worth budgeting for.

My Tap Water Results: NYC vs. LA

Anyway, I did it; I ordered the kits, collected the samples, and sent them off. The results really shocked me. Spoiler alert: NYC water was much “cleaner” than my LA water. The LA water analysis came back with 8—EIGHT!—flagged health concerns, one taste concern, and one concern about my plumbing.

Let’s cut to the chase and get to the health concerns. There were 8 substances found in significantly higher levels than the guidance level standard for health and safety (which is the most protective human health benchmark used among public health agencies for a contaminant); they included:

- Arsenic

- Bromodichloromethane

- Chloroform

- Dibromochloromethane

- Fluoride

- Lead

- Lithium

- Uranium

Most of these are used as part of the disinfection process, but the EPA sets a maximum level above which the risks outweigh the benefits.

Understanding the Health Risks of Contaminants

This is what my testing company, GoSimplelab, noted about chloroform:

“Chloroform is a member of a group of disinfection byproducts called trihalomethanes (THMs) that form in water treated with chlorine and is generally the most abundant THM formed in drinking water. It is produced naturally by marine algae and soil processes in significant quantities and is also used as a laboratory solvent and found in small amounts in many common products. Chloroform is readily volatile; thus, all routes of exposure (ingestion, inhalation, and transdermal [absorption]) are relevant if one is exposed via drinking water. Known health effects of elevated chloroform exposure include kidney, liver, immune system, and developmental toxicity and increased risk of cancer.”

Wow.

For arsenic, the GoSimplelab results summarizes this way:

“The EPA drinking water limits for arsenic are based on adverse effects to the skin and circulatory systems as well as an increased risk of cancer. Long-term exposures to low levels of arsenic concentrations in drinking water are associated with an increased risk for several types of cancer including bladder, GI tract, kidney, liver, lung, pancreas, and skin.

Other noncancerous health effects of long-term exposure to arsenic found in epidemiological studies include developmental effects, cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, ocular effects, impaired immune response, neurotoxicity, and diabetes. High doses of arsenic can be lethal, and lower (yet still elevated) levels of arsenic exposure can result in acute health effects. The first signs of arsenic exposure may include a metallic taste in the mouth or a garlicky odor on the breath.

This is followed by symptoms that include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, muscle cramps, weakness, tingling, and numbness. These acute impacts are unlikely at concentrations found in drinking water.”

Double wow.

What to Do If Your Water Fails The Test

Obviously, I was not pleased with the results of my LA tap water test. But the testing was/is the easy part.

There are a number of ways to test your drinking water. Some towns/cities offer free testing at the local health department, and numerous companies offer testing at a variety of price points. What to do AFTER you get results (if the results are bad) is really the question.

I decided to switch to glass-bottled water (more expensive but much safer) and am looking into getting a filter under my sink in LA. More expensive is not necessarily better when it comes to these filters, so make sure you do your research. I am still doing mine—and will keep you posted!

Also, as scary as these kinds of reports can be, remember that most risks associated with elevated levels of chemical contaminants are due to lifetime exposure to said chemical, and that the general principles of toxicology center largely on duration of exposure, dose of the toxin, and one’s individual susceptibility to this exposure.

That’s another way of saying that just because high levels are detected does not automatically mean that adverse health effects should be expected.

My NYC water fared better, and testing revealed nothing terribly scary. But the results in LA really made me nervous. I started thinking about how much we were using that tap water: to cook, to make coffee or tea, to give to our dog, Mason.

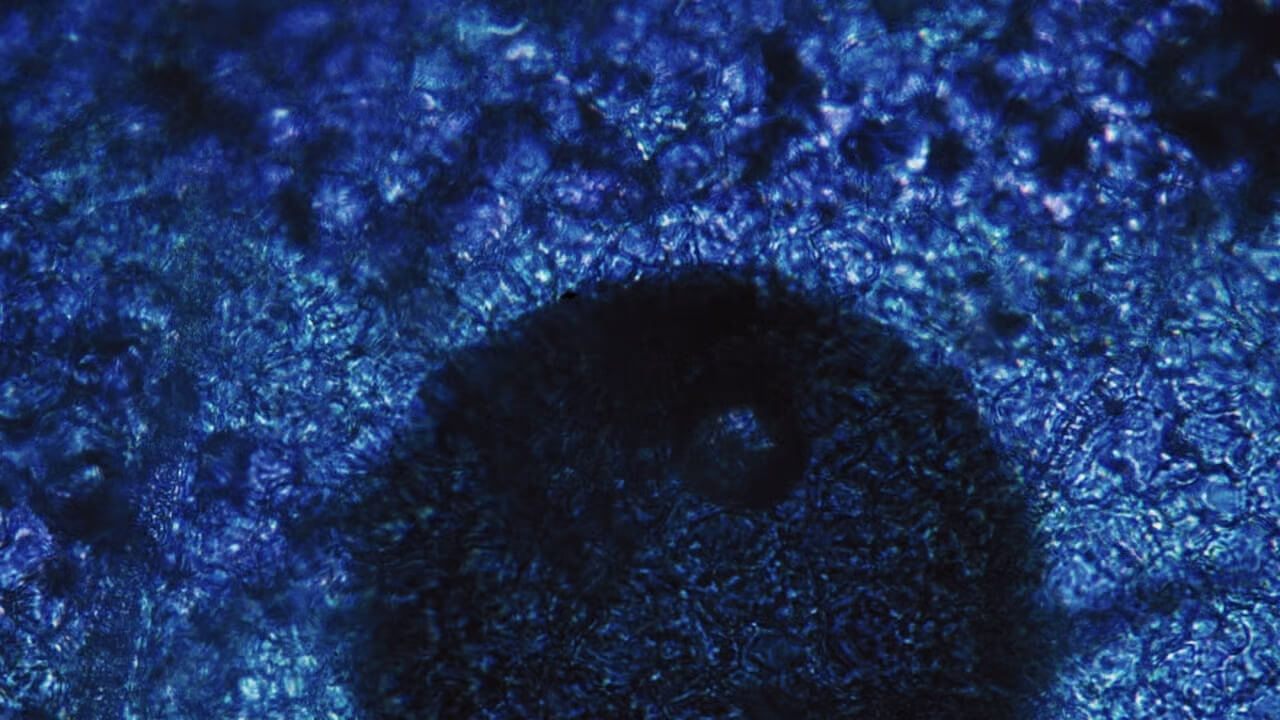

I’ll admit it: At this point, I may have ventured down the proverbial rabbit hole a bit. I don’t generally drink enough water as it is; now I had to be concerned about my tap water (as many people already are), and I felt slightly panicked about WHATEVER I was doing with water.

So, your dose of honesty for today is twofold: When you test anything, make sure you are prepared if that test doesn’t turn out as you expected or hoped it would! But if the test involves something as vital to your health as the quality of—or potential harm that may be caused by—the water you drink, do the research, consult the experts, and spend the money if necessary to make it safe.

How to Start Testing Your Own Water

Want to learn what’s in YOUR water? The best place to start is with some research. And in doing mine, I found some really helpful information on the Consumer Reports website. From what these tests should be evaluating to which actually work the way they should, the editors have provided a good, basic guide to starting the process.

The link will also take you to other resources—about bottled water, PFAs, and an extensive water filter buying guide. Click here to learn more.

To find out how safe your water is, check this out: Learn more.